When the verdict came down, I felt like the world had flipped upside down. The gavel hit the bench, and in that moment, my life as I knew it ended. Two years in prison for a crime I didn’t commit.

A theft I hadn’t even thought about, a situation I had no part in, yet somehow the evidence, circumstantial and misleading, was enough to convince a jury to take my freedom away. I remember staring at the judge in disbelief, trying to comprehend how someone could punish me for something I hadn’t done. My family was silent, my friends confused, and strangers on the street whispered as I was led away.

The first months were the hardest. Prison is not only a place of confinement—it is a place where your mind can feel imprisoned long before your body ever is. The smell of disinfectant mixed with sweat, the clang of metal doors, the constant echo of shouting, crying, or laughter from someone who was equally trapped. I learned quickly how to stay silent, how to avoid conflict, how to make myself invisible. But invisibility doesn’t protect you from the emotional toll. Nights were the worst. Lying on a thin mattress in a tiny cell, hearing the guards’ footsteps outside, I replayed my life endlessly, questioning every choice that had somehow led to this injustice.

And yet, through it all, there were visitors. Not many, but the ones who came were persistent. They showed up every month, exactly on visiting day, dressed neatly, bringing small packages: magazines, snacks, or letters. Each time, I forced a smile, nodded politely, and allowed myself to hear their words. I wanted to believe they were there for me, but deep down, it became clear—they were expecting something else. They weren’t just visiting out of concern. They were visiting with the quiet assumption that forgiveness was owed. That the wrong they had done to me—or at least the role they had played in this injustice—would be excused with a smile and a hug.

At first, I tried. I tried to believe in their intentions. I wanted to believe that even if my freedom had been stolen, the people around me could somehow make it right with a few gestures. But every visit became a reminder. A reminder of the betrayal, the damage, the months of lost time, the stolen opportunities, the fear that had lodged itself permanently in my chest. Their eyes, hopeful and almost pleading, seemed to say, Forgive us, because we can’t handle your anger.

Anger, I realized, was a luxury they hadn’t yet lost. I had been forced to carry it alone, in silence, in every step I took through those grim halls. And while I had managed to control it, to survive, to endure, I refused to be coerced into forgiveness by the mere consistency of their presence. Forgiveness isn’t owed, I thought bitterly. Not to people who hurt you and then expect your suffering to be erased by a smile.

Months stretched into years. I learned the rules of survival. I learned to befriend certain guards, to avoid others. I learned to read the moods of inmates, to predict conflicts before they erupted. I spent hours reading, writing, exercising, trying to keep my mind sharp. And yet, every time someone familiar approached the visiting window, the old frustration returned, a spike of fire in my chest that refused to die down. Their faces, their voices, their polite smiles—it was all a quiet assault on my autonomy. They assumed they had the right to dictate how I processed the wrongs done to me.

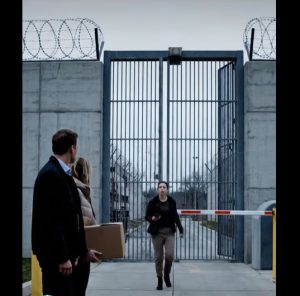

It wasn’t until the last few months that something shifted. I began to understand that forgiveness is not about their relief—it’s about my peace. I began to see that the visits were both a test and a torment: a test of my patience, a torment of my unresolved feelings. And I made a choice. I would forgive, but not for them. I would forgive for me.