I sold the bike two weeks after the funeral.

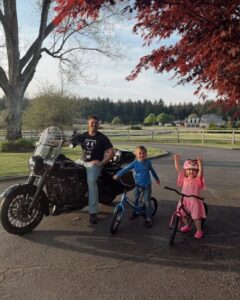

I didn’t wait long. I just couldn’t face it. The bike sat there in the garage, haunting me with memories. Every curve of that black Harley reminded me of Mia—her chin resting against my back, her laughter in my ear, her arms around my waist as if I was the only thing keeping her anchored to this world. She had this quirky pink helmet, scratched and worn, totally mismatched with everything else we wore. Riding was our escape—our rebellion, our therapy, our date nights all rolled into one.

But when the accident happened—when a drunk driver ran a red light and took her from us—I parked the bike and never touched it again. I couldn’t. Riding without her wasn’t just painful; it felt wrong. And more than anything, it felt dangerous. I had two kids to look after now. I couldn’t risk it.

So, I let it go. I told myself it was just a machine. Letting go was part of moving on. That’s what they say, right? “You have to move on.”

But sometimes, moving on is harder than it sounds.

I remember catching my son, Jace, once—he’s ten—running his hand along the bike before I sold it, whispering to it like it could hear him. My daughter, Lila, who’s thirteen and acts like she’s thirty, stopped drawing in her sketchbook for days after it was gone. They didn’t say much, but I could tell. They saw that bike for what it was: a symbol of a time before the world cracked open.

So, when they burst through the front door yesterday, shouting like the house was on fire, I knew something was up.

“Dad! There’s a man on your bike!”

“Yeah! The black Harley—flames on the tank! Your design! You painted that!”

I followed them outside, my heart pounding. There, at the far end of the block, a man in his forties was riding slowly down the street, like he had nowhere else to be. The bike gleamed as though it had just been polished—custom flames still fresh, orange and red licking across the tank like they were alive.

It was mine.

“Looks like it’s in good hands,” I muttered, more to myself than to them. But the truth? My stomach twisted like I’d just seen an ex with someone new. It wasn’t jealousy—it was something deeper. Grief with a fresh coat of regret.

The next morning, while I scrambled eggs and burned the toast, the kids were unusually quiet, exchanging glances but not speaking. And then I heard it—that familiar growl of a V-twin engine.

I stepped outside.

There he was again. The man from yesterday. Helmet off now, revealing sandy hair streaked with gray, sun-creased eyes, and a warm smile that didn’t quite match the leather jacket and fingerless gloves.

“Morning,” he called. “Mind if I talk to you for a sec?”

I hesitated, then walked down the porch steps.

“My name’s Rick,” he said, offering a hand. I shook it.

“I’m Nate.”

“I know,” he nodded. “Your kids told me all about you yesterday. Didn’t take long to connect the dots.”

I raised an eyebrow. “They talk to strangers now?”

He laughed. “I was a stranger until I told them I had your bike. Then I was practically a superhero.”

I glanced at the Harley. “You’ve kept it in great shape.”

“Wouldn’t dream of doing otherwise,” he said, reaching into his jacket pocket. “Look, I know this is a little odd, but after meeting your kids, I felt like you should have this.”

He handed me a folded flyer. It was for a biker’s club: *The Iron Circle Riders*. Beneath the logo, it read: *Weekend rides. No one rides alone.*

“We meet every Sunday,” Rick explained. “Nothing crazy. Just a group of people who’ve been through things—grief, divorce, PTSD, you name it. We ride together. We look out for each other. It’s therapy with chrome and throttle.”

I stared at the flyer. “What does this have to do with me?”

He shrugged. “Your kids told me why you sold the bike. I get it. I really do. I lost my brother to the same kind of thing five years ago. For a while, I thought I’d never ride again. Then I found this group.”

He paused, looking at me. “If you want your bike back, I’ll sell it to you—same price I paid. No markup. But only if you come on one ride. See what it’s like. If you hate it, no hard feelings.”

I took a second to respond.

“You’d sell it back?” I asked.

“I’d rather it go to someone who understands,” Rick said. “Besides, it still kind of feels like your bike.”

I didn’t say yes right away. But I didn’t say no either.

That Sunday, I showed up at a gas station off Route 7, wearing my old boots and a jacket that still smelled faintly of oil and leather. Rick was already there, nodding at me with that same calm grin. The other riders trickled in—men and women, young and old, some with patches, some with nothing but road grime and tired eyes. I expected noise and bravado, but it was quiet. Respectful. Like a church made of exhaust and asphalt.

We rode forty miles together through winding roads and hills. I didn’t speak much. Didn’t need to. The wind did all the talking.

When we stopped for lunch at a roadside diner, a woman named Tasha sat beside me and asked about Mia. I hadn’t said her name in weeks. I surprised myself by telling her everything—how we met at a gas station, how she taught me to salsa in the living room, how she died in an instant, and took a part of me with her.

“You know what I think?” Tasha said, resting her hand on my forearm. “I think if she saw you today, she’d be proud you got back on.”

I didn’t answer. But I didn’t argue either.

When the ride ended, Rick handed me a key.

“It’s yours if you want it,” he said.

I looked at the bike, then at my hands—shaking just a little. Not from fear, but from something new. Anticipation.

“I want it,” I said.

That night, I pulled into the driveway. Jace and Lila were already on the porch, waiting like it was Christmas morning.

“You bought it back?” Lila gasped.

“I did,” I said, tossing them each a helmet.

“We’re going for a ride?” she asked.

“Only if you promise to hold on tight,” I smiled.

We didn’t go far—just a few blocks, circling the neighborhood—but the sound of their laughter, the wind against my face, it was like breathing after holding it for too long.

Mia was still gone. That hadn’t changed. But something in me had shifted. The grief was still there, sure—but now, it had room to ride beside something else: hope.

So yeah, I sold the bike two weeks after the funeral. But maybe letting it go wasn’t the mistake.

Maybe the mistake was thinking I had to ride alone.

**Would you have taken the bike back?**